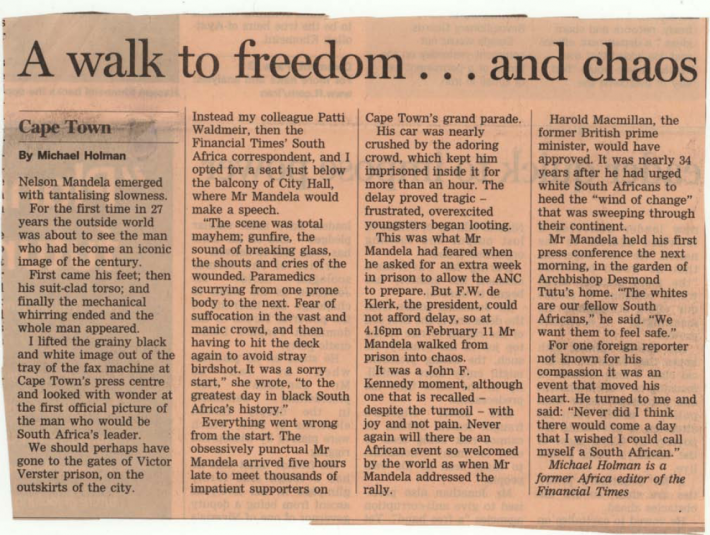

Nelson Mandela emerged with tantalising slowness.

For the first time in 27 years the outside world was about to see the man who had become an iconic image of the century.

First came his feet; then his suit-clad torso; and finally the mechanical whirring ended and the whole man appeared.

I lifted the grainy black and white image out of the tray of the fax machine at Cape Town's press centre and looked with wonder at the first official picture of the man who would be South Africa's leader.

We should perhaps have gone to the gates of Victor Verster prison, on the outskirts of the city. Instead my colleague Patti Waldmeir, then the Financial Times' South Africa correspondent, and I opted for a seat just below the balcony of City Hall, where Mr Mandela would make a speech.

"The scene was total mayhem; gunfire, the sound of breaking glass, the shouts and cries of the wounded. Paramedics scurrying from one prone body to the next. Fear of suffocation in the vast and manic crowd, and then having to hit the deck again to avoid stray birdshot. It was a sorry start," she wrote, "to the greatest day in black South Africa's history."

Everything went wrong from the start. The obsessively punctual Mr Mandela arrived five hours late to meet thousands of impatient supporters on Cape Town's grand parade.

His car was nearly crushed by the adoring crowd, which kept him imprisoned inside it for more than an hour. The delay proved tragic - frustrated, overexcited youngsters began looting.

This was what Mr Mandela had feared when he asked for an extra week in prison to allow the ANC to prepare. But F.W. de Klerk, the president, could not afford delay, so at 4.16pm on February 11 Mr Mandela walked from prison into chaos.

It was a John F. Kennedy moment, although one that is recalled - despite the turmoil - with joy and not pain. Never again will there be an African event so welcomed by the world as when Mr Mandela addressed the rally.

Harold Macmillan, the former British prime minister, would have approved. It was nearly 34 years after he had urged white South Africans to heed the "wind of change" that was sweeping through their continent.

Mr Mandela held his first press conference the next morning, in the garden of Archbishop Desmond Tutu's home. "The whites are our fellow South Africans," he said. "We want them to feel safe."

For one foreign reporter not known for his compassion it was an event that moved his heart. He turned to me and said: "Never did I think there would come a day that I wished I could call myself a South African."

Michael Holman is a former Africa editor of the Financial Times

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2013.

News & Comment

11 February 2010

Filed under News & Comment

A leader welcomed by the world